What is Human Trafficking?

Human trafficking is generally understood within the United States to mean:

- The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (sex trafficking), in which a commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such act has not attained 18 years of age; and

- The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.

This crime is far more pervasive than previously understood. In 2020, 11,193 situations of human trafficking were identified through the United States National Human Trafficking Hotline. Globally, an estimated 24.9 million people are subjected to human trafficking, which generates an estimated $150 billion annually in illicit profits.

Traffickers often manipulate adult or child victims’ difficult economic conditions, instability in housing, substance abuse issues, or lack of family support to isolate victims and make them wholly dependent upon their traffickers. Those who engage in the sex trafficking of minors target vulnerable children and gain control over them using a variety of manipulative methods.

Characteristics of Human Trafficking

Who is victimized?

Human trafficking victims can be of any age, race, ethnicity, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, nationality, immigration status, cultural background, religion, socio-economic class, and education attainment level.

Individuals particularly vulnerable to human trafficking in the United States include children in the child welfare system or who have encountered the juvenile justice system; runaway and homeless youth; unaccompanied children; persons who do not have lawful immigration status in the United States; American Indians, Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders, and other indigenous peoples of North America.

Other vulnerable populations include Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and Intersex (LGBTQI+) individuals; migrant laborers; persons with disabilities; and individuals with substance use disorder. While girls, women, and LGBTQI+ community members are notably more vulnerable, sex and labor traffickers also regularly target boys and men.

There are strong indicators that Black and Latino women and girls are disproportionately represented among human trafficking victims and survivors identified in many communities, although there is a dearth of nationwide data related to people of color.17 There are other factors that correlate with a higher risk of human trafficking victimization, such as recent migration or relocation, substance misuse, unstable housing, abuse, childhood trauma, and mental health issues.

One of the biggest challenges facing law enforcement and service provider professionals is the ability to accurately identify human trafficking victims, which is due to several factors, including the level of trust that victims bestow in these professionals.

A 2019 Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) study found that about 72 percent of calls to the National Human Trafficking Hotline related to sex trafficking, 11 percent related to labor trafficking, four percent were both, and 13 percent were unspecified. According to a 2019 FBI study based on data derived from its investigations in the United States between 2015 and 2017, 80 percent of human trafficking cases that were investigated involved victims of sex trafficking, 19 percent were victims of labor trafficking, and one percent involved both sex and labor trafficking. Historically, labor trafficking has been more difficult for law enforcement to detect than sex trafficking.

Who are Human Traffickers?

Human traffickers come from a wide variety of backgrounds and demographic categories. Human traffickers can be relatives, friends, individuals who are politically connected in their country of origin, individuals operating alone, or those in loosely affiliated groups or as part of gangs or transnational criminal organizations. Many times, prosecutors obtain convictions of human traffickers and their associates for crimes other than human trafficking, such as money laundering or fraud. Human trafficking networks

may be linked to other criminal activities, such as kidnapping, extortion, racketeering, foreign corrupt practices, production of counterfeit goods, prostitution, drug trafficking, money laundering, document fraud, visa fraud, immigration-related crimes, and public corruption.

More generally, human traffickers often operate a range of illicit enterprises both in the United States and abroad. For example:

- Transnational criminal organizations engage in human trafficking, frequently in conjunction with other criminal activities.

- The Zhao Wei drug trafficking organization engages in human trafficking to generate funds to further its other criminal activities.

- MS-13 engages in human trafficking both domestically and transnationally.

- Mexican origin transnational criminal organizations engage in sex trafficking to facilitate other illicit activity.

- Multiple European countries have documented transnational organized crime operations that exploit both European nationals and migrants in sex and labor trafficking, including forced criminality such as pickpocketing and the distribution of narcotics.

- Terrorist organizations – including Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, Boko Haram, and Al-Shabaab engage in human trafficking crimes.

- State actors such as Afghanistan, Burma, Cuba, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Eritrea, Iran, the People’s Republic of China, Russia, South Sudan, Syria, and Turkmenistan engage in state-sponsored forced labor or sex trafficking.

How do the human traffickers operate?

To control their victims, human traffickers may use tactics and techniques such as physically isolating their victim, emotionally manipulating a victim through false promises of love, threatening a victim with various forms of harm, including from the legal system, such as deportation or arrest, and manipulating a victim’s substance use. Human traffickers also engage in debt bondage.

Prospective victims are often led to take on debt, ostensibly to support the costs of accessing a “good” job, via credible, but false, promises of a better situation. Then, human traffickers and their co-conspirators ensure that the debts are sufficient for the victim to fear that if the debt is not repaid, the victim or their family will suffer serious consequences threatening their life, health, welfare, or property.

Human traffickers use diverse modes of transportation to facilitate their illicit activities. Human traffickers also use technology to facilitate the trafficking, such as online social media platforms to recruit and advertise human trafficking victims and livestreaming platforms to facilitate child sex trafficking.

Law enforcement continues to make strides in interdicting illicit online activity including the seizure of online platforms that advertise commercial sex involving human trafficking. These seizures severely disrupt traffickers’ operations and those facilitating the illegal activity. However, law enforcement must invest in the latest tools and technology and remain vigilant to the adjustments traffickers make to avoid detection, including the movement of internet servers overseas.

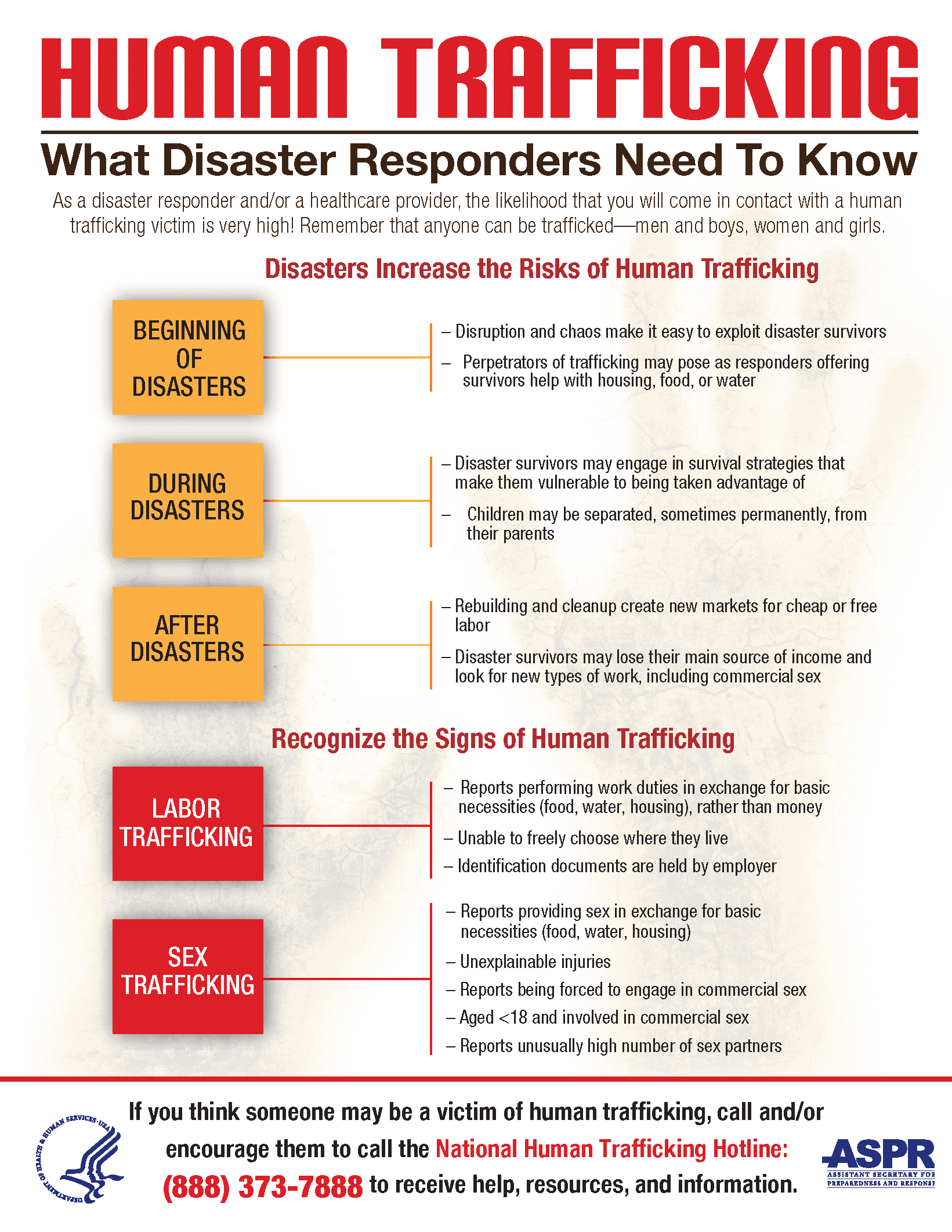

Certain environments are

more likely to enable human traffickers to conduct and profit from their criminal exploitation. Human traffickers take advantage of breakdowns in the rule of law and weakened social support caused by conflict, natural disaster, and other crises to recruit victims. Corrupt government officials also enable human traffickers; for example, officials may accept bribes from labor brokers engaged in deceptive practices. These breakdowns are compounded when governments are actively hostile to civil society, precluding partnerships with NGOs that otherwise could reinforce counter-trafficking efforts.

The weakness of government institutions fuels not only impunity, but also the desperation of individuals eager to support their families and, in some cases, simply to survive. Human traffickers exploit these needs in order to lure victims with false promises of a better situation in the United States or elsewhere. For example, Mexico is the top origin country in human trafficking cases involving foreign national victims in which the United States is the destination. Recent cases involved sex trafficking enterprises linked to a region in central Mexico, which recruited young victims who were then smuggled into the United States and compelled into commercial sex acts in New York, Atlanta, and other cities.

In cases where human traffickers have recruited individuals outside the United States with the intent of exploiting them in the United States, they may be moved through intermediary or “transit” countries, sometimes for extended periods, during which victims may also be forced into labor or commercial sex. Transit countries are chosen for the geographical location and are usually characterized by weak border controls, proximity to destination countries, corruption of immigration officials, or affiliation with organized crime groups that are involved in human trafficking and human smuggling.

Financial activity from human trafficking activities can intersect with the formal financial system at any point during the recruitment, transportation, and exploitation stages. The illicit proceeds from human trafficking can include income associated with logistics, such as housing and transportation of victims, as well as earnings from the exploitation of victims.

How You Can Help

Know your Human Trafficking jurisdiction by partnering with your local law enforcement and human social services partners and learn more about Human Trafficking by going to dhs.gov/blue-campaign.